Gateway to the sepulcher of Shah Wali Allah

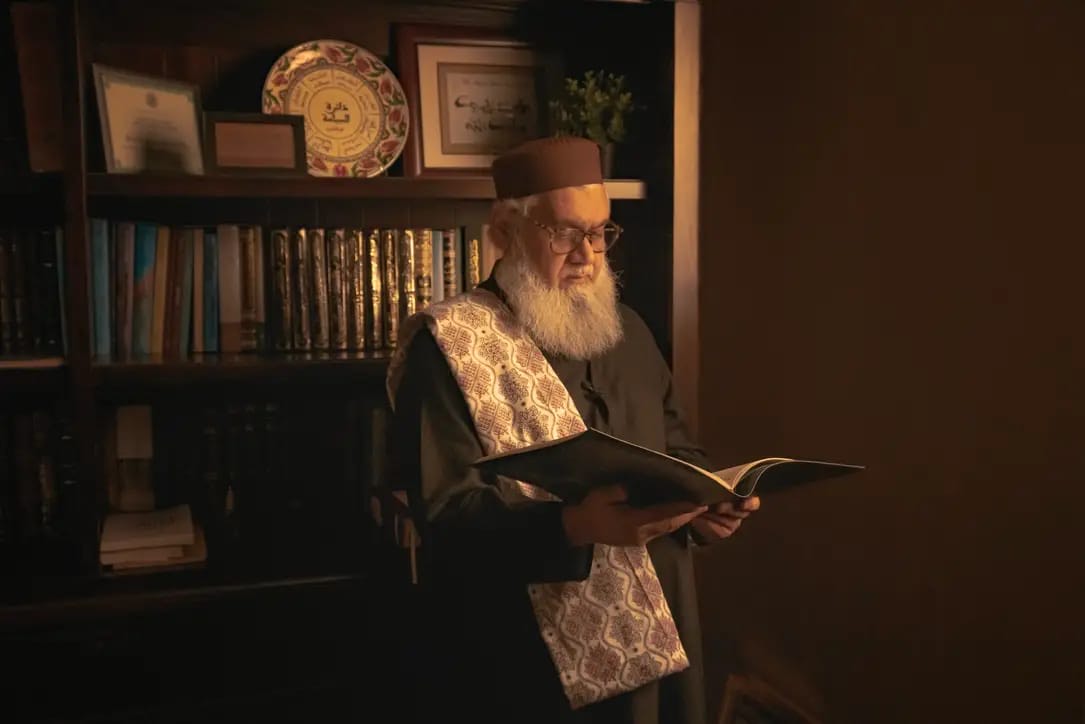

Shaykh Amin Kholwadia teaching Tafsir at Darul Qasim College’s Glendale Heights Campus

In this sweeping and meditative essay, Saaleh Baseer traces the intellectual and spiritual legacy of Shah Wali Allah of Delhi, the 18th-century scholar who became the axis of Islamic thought in South Asia, and follows its reverberations through the centuries to Shaykh Amin Kholwadia, founder of Darul Qasim College.

Through poetic language, historical narrative, and philosophical reflection, Baseer illuminates how Shah Wali Allah’s synthesis of Hadith, philosophy, and Sufi metaphysics shaped not only the Deoband movement but also the contours of Islamic scholarship that would later take root in the West. The essay moves fluidly from Mughal Delhi to modern Chicago, exploring how one scholar’s intellectual vows of reconciling reason and revelation, the sacred and the social, found a living continuation in America through Shaykh Amin’s teaching and vision.

A rare blend of memoir, history, and metaphysical inquiry, How an Anglo-Gujrati Mufti Kept the Vows of Shah Wali Allah in America invites readers to rediscover the luminous continuity of Muslim thought, spanning from the sepulchers of Delhi to the classrooms of Glendale Heights.

————————–

***This essay was originally published by Traversing Tradition: https://traversingtradition.com/2025/11/10/how-an-anglo-gujrati-mufti-kept-the-vows-of-shah-wali-allah-in-america/

The world of Shah Wali Allah and the Mughal scholars he inspired invites deeper exploration.

Enroll in Mawlana Saaleh Baseer’s MARS 107 course: The Mughal Imperium, and study the historical, philosophical, and spiritual forces that shaped an age of renewal in the Muslim world.

Mawlana Saaleh Baseer is a doctoral candidate in Harvard’s dual program in History and Middle Eastern Studies (entered 2023). His research focuses on Hanafi legal theory (uṣūl al-fiqh) and the political theology of the Mughal/Timurid and Ottoman empires, as well as post-classical Hanafi thought in Central Asia, the Ottoman Arab provinces, and Mughal India. He completed the six-year Dars-i Niẓāmī curriculum in South Africa, receiving ijazah in Arabic, Islamic law, ḥadīth, tafsīr, and theology, and later earned a BA in History at Columbia University. He also studied and served for three years at Darul Qasim College, authoring fatwas in Islamic finance, bioethics, and related fields.